Oskar Jacek Rojewski,

The prosopographical approach for the study of Valets de chambre at the court of Philip the Good and Charles the Bold

The title Valet de chambre appears for the first time, in the French court on the second half of the Fourteenth century. This title showed a closed relation and allowed direct communication between the servant and the sovereign. Later on the same model was adapted to other courts that followed the french tradition, like the court of dukes of Burgundy in the Fefteenth century. This study aims to identify the Valets de chambre serving at the court of Philip the Good and Charles the Bold applaying a prosopographical approach in order to gather as much information as possible about this social group. Thanks to the analisis of «Recette general des finances» and ducal ordinances from : 1426, 1433, 1438, 1445, 1449 and 1458 it is posible to describe the group of people that enjoyed the privilege of serving at the court.

The title Valet de chambre appears for the first time, in the French court on the second half of the Fourteenth century. This title showed a closed relation and allowed direct communication between the servant and the sovereign. Later on the same model was adapted to other courts that followed the french tradition, like the court of dukes of Burgundy in the Fefteenth century. This study aims to identify the Valets de chambre serving at the court of Philip the Good and Charles the Bold applaying a prosopographical approach in order to gather as much information as possible about this social group. Thanks to the analisis of «Recette general des finances» and ducal ordinances from : 1426, 1433, 1438, 1445, 1449 and 1458 it is posible to describe the group of people that enjoyed the privilege of serving at the court.

Texte intégral

1. Introduction1

1Across XIXth and XXth centuries historiographical movements generated specific kinds of studies on the Late Medieval Age and the beginning of the Renaissance. These studies resulted in an ideological interpretation of the artistic tendencies during XVth century, and lead to a rather ambiguous understanding of the phenomenon2. Indeed one relevant aspect of Late Medieval Art research is the role of the artist and his position in society ; according to the historiography it is posible to distinguish two types of artistic production : on the one hand the workshops that realized the orders of the bourgeois (mainly devotional altars and polyptychs) and, on the other hand, artistic production under court’s patronage, that is to say, artists maintained under royal or ducal protections. Interestingly, art historians analysed the relation between artists and sovereigns in order to understand how much the ruler was able to interfere with the creation process and the final result, considering the two former types of artistic production as the major major factor.

2Simultaneously, the phenomenon of singling out the artist from the rest of the society and from the rest of the court can be observed at the end of XIIIth century as in the case of French, English or D’Anjou’s courts where some artists had been honoured with the title of pictores regis or peintres nostre sire. However, even if it is recognised that these artists realised orders for art pieces, unfortunately, it is not possible to better understand the relation between these artists and the court, since none of them was directly associated with it.

3Later on, at the beginning of XIVth century, artists working for the courts could reach the title of «valeti et alii hospitii» and «valeti et familia hospitii», similarly to other servants who did not proceed from the noble class3.

4The mention Valet de chambre appears for the first time at the French court between 1356 and 1359, referring to the painter Girard d’Orleans, showing a stronger relation to the King, like other first class servants, that allowed direct communication with the ruler4.

5Similarly, in the case of the court of the Count of Flanders Louis of Male, the artist Jean de Hasselt was mentioned in 1378 with the rank of paintre de MS. Apparently after 1384, and still with the same title, de Hasselt continued working for the Duke of Burgundy, Philip the Bold5. In fact, only the artist’s successor, Melchior Broederlam, is documented to have reached the title of paintre de MS de Bourgogne et varlet de chambre at least from the 4th of November, 13686.

6Furthermore, studies on the ritual court and ceremonial acts of the Duchy of Burgundy are possible thanks to the erudite narration of Olivier de la Marche and his l’Estat de la Maison du duc Charles de Bourgogne written in 1473. Being part of the close entourage of the duke and maître d’hôtel, the author described the court’s structure, explaining the hierarchy, the order of the organization, the interactions between the different ranks as well as the symbolism present in the court7. At the same time, the chronicler fascinatingly explored the court environment ; the official as well as the private one.

7De la Marche does not name all the personages, but offers a detailed description of the functioning of the court, and focusing on the prestige of its patron. Interestingly for this study, De la Marche described the valet de chambre according to the relevance of their profession. Thus, Valets de chambre are mentioned after physicians and garde de joyaux and before chefs and musicians. Nevertheless the narration gives some clues about the definition of valet de chambre :

Le duc a bien quarante varletz de chambre, don’t la plus part servent tousjours, et les autres sont comptes par terme, et servant iceulx en la chambre en diverses manieres, les barbiers en leurs estaz, les chaussetiers, tailleurs, cousturiers, fourreurs et cordouaniers, chascun en leurs estaz. Les paintres fons les cottes d’armes, baniers et estandars ; les aultres varletz de chambre servent de faire le lict, et à mettre à point le chambre ; et doibt le fourrier battre et escourre le lict, c’est à sçavoir la coustelle et le coussin où le prince doit gestir ; et pour ce seullement est le fourrier nommé varlet de chambre ; et doibvent les principaulx estendre les linceux et la couverure. Et deoibt le sommellier tenir une torche en ses mains pour veoir faire de lict, et après refermer les courdines. Et doibt ung quatre sommelliers garder le lict, jusques à tant que le prince soit couchié8.

8The author indicates a supposition of the amount of servants with the rank of Valet de chambre and differentiates two kinds of courtiers : some of them attending the court every day and some others throughout the year with indications of their specific professions. In addition, de la Marche notes a difference between professionals that were able to practice their work at the court, and the servants who had obtained the privilege of participating during the ceremony of lying down the duke, and describes their function9.

9This study applies elements of proper methodology often utilised in the study of history - prosopograhy10, with the intention of describing the role and position of the court artist, a topic considered as apt for Art History studies. This analysis aims firstly to identify the largest possible set of Valets de chambre serving in the period, and secondly to gather as much information as possible for each servant in order to reach a deeper understanding of two main subjects. Firstly, the period of attendance at the court as part of the circle of the Valets de chambre and, secondly, the profession as reported by the sources. It is important to highlight that this study is limited to the rank of Valet de chambre de Mon Dit Segnor, excluding the same kind of servants working for the duchesses and for the heir, the Count of Charolais.

10The first identification of the group is based on the published transcriptions of the «Recette general des finances» of the Burgundian Duchy from period 1419-1477. This corpus contains the volumes edited by Michiel Mollat11, covering two full years (1419-1420), those published by Wernier Paravicini12 covering the period 1467-1477, and the supplementation of the sources edited by Leon de Laborde13, which collected accounts related to the artistic production and patronage at the Burgundian court. A full prosopographical study could not be made on the «Recette general des finances» since they are not completely preserved14. As a result the sampling set was broadened to include Valets de chambre cited in the corpus of the court ordinances from years : 1426, 1433, 1438, 1445, 1449 and 145815.

11Once sampling sets were obtained, the figures identified with all known variations of their names were researched in the Prosopographia Burgundica16 project, an online catalogue of thirteen published Instruments and ten studies on the Burgundian Court, as well in the Prosopographia Curiae Burgundicae17 project ; another online database that explores 5800 accounts of incomes and expenditures of the court.

2. The state of the art

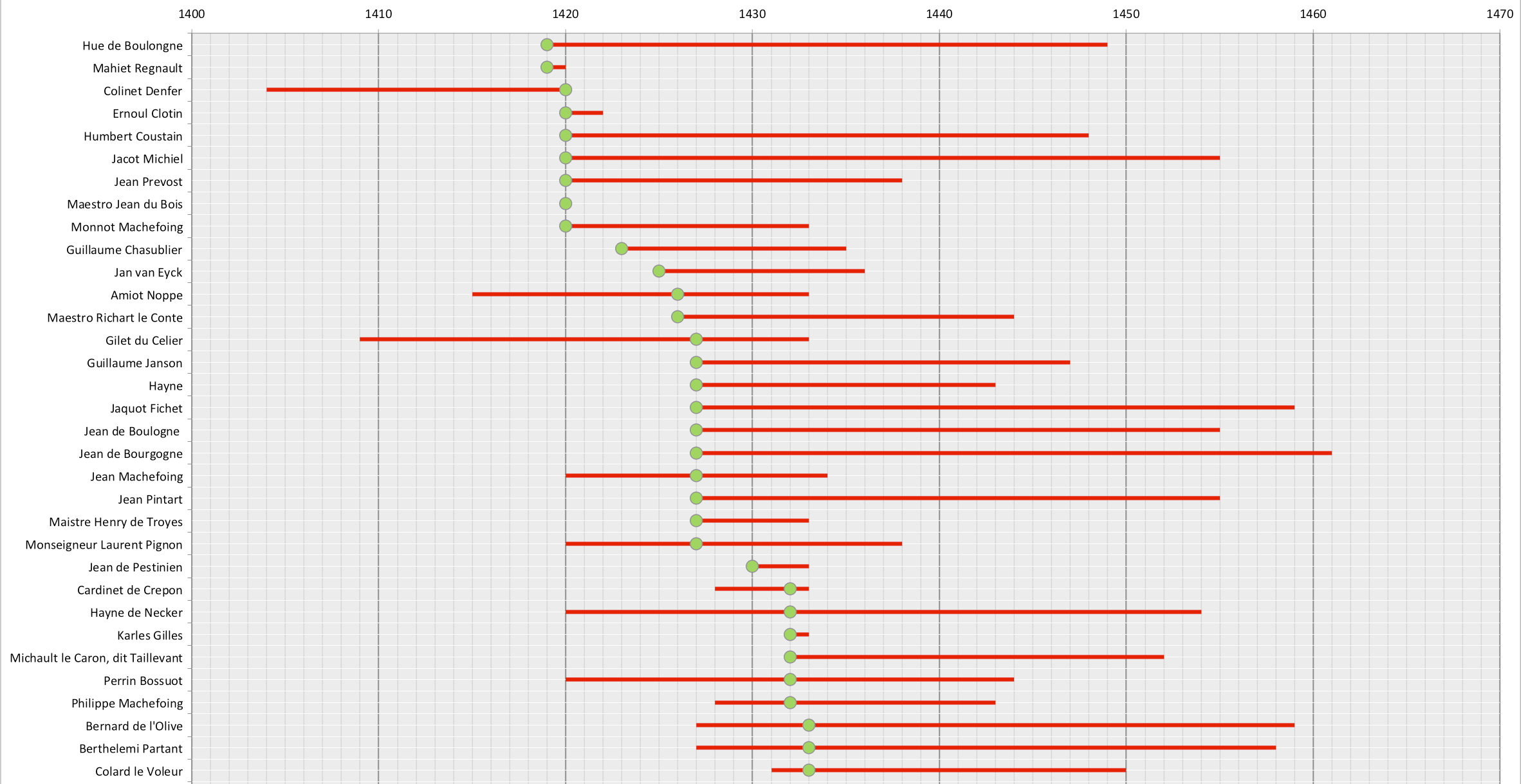

12The fact that many artists of the Burgundian court had reached the title Valet de chambre prompts many art historians to reflect on the functions related to this title18. Ruth Massey Towel analysed the court environment and the artistic production charged by Burgundian dukes. She discussed some Valets de chambre - Melchior Broederlam, Claus Sluter and Van Eyck – but she considered the title as a mere description of the position of the court artist ; she argued that the Valet de chambre at the Burgundian Court had to be an artist19. This idea was applied to later studies on «Valets de chambre» of the Bourgundian Court such as in the case of Claus Sluter ; in catalogues dedicated to his artistic production we can locate mentions such as « From 1389 to his death he was Court Sculptor, with the rank of valet de chambre »20. Yet the image we receive of Sluter’s work at the court as Valet de chambre seems to be a simplification, due to a contemporary interpretation of his duties at the Burgundian court.

13Hugo Van der Welden analysing the figure of Gerard Loyet, goldsmith and Valet de chambre of Charles the Bold, tried to explain whom the valet de chambre at the Burgundian court was. First of all, analysing the Comptes de l'argentier he was able to prove that Loyet, had obtained the title of valet, even though, in the chronicles by Olivier de la Marche, goldsmiths were not cited as a category of artisan included in the list of Valets de chambre working at the court of Charles of Burgundy21. Secondly, he demonstrated that the artistic activities of Valets de chambre were conducted during everyday life, and especially during festivals and ceremonies at the court. Nevertheless, as a final result Van der Welden assumes that only the most skilled artists could reach the rank of Valet de chambre, demolishing the absolute credibility of Olivier de la Marche’s reports about the valets, but confirming the connection between Valets de chambre and artists.

14A different understanding of the role and the relevance of Valet de chambre was brought by Bart Fransen while describing the Burgundian diplomatic expedition to the court of Portugal for the arrangement of the marriage between the duke and the princess of Portugal. According to his studies, Van Eyck’s participation in the secret expedition in order to paint a portrait of Isabel of Portugal, demonstrates not only the trust the Duke placed in his artistic skills, but the high rank of the Valet de chambre in the Burgundian Court as well as the trust awarded to the valet by the duke himself22. In fact, all the other officials participating in that expedition were part of the very highest level of the court structure. Fransen’s research shows that Valet de chambre had not only artistic tasks at the court but he could be asked to accomplish diplomatic tasks as well.

15Finally, Dominique Vanwijnsberge, looking at some valets de chambre and book iluminators related to the administration of the ducal library as examples, supported the theory that the valet de chambre had to be a createor of images of writter at the court23.

16Considering the muddled situation concerning the knowledge of the social definition of valets de chambre, this article proposes a prosopographical approach to the theme in order to detail the variety of tasks and the social position of the Valets de chambre at the Burgundian court. More specifically this study aims to define which professionals could join the circle of the Valet de chambre at the court of Philippe the Good and Charles the Bold, from 1419 to 147724.

3. The prosopographical approach

17The first analysis of the «Recette general des finances» aimed to identify all mentions of the title Valet de chambre from 1419 to 147725. This operation allowed an identification of the accounts referring specifically to interactions between courtiers and the ducal administration, thus reducing the amount of accounts and cédules in the study to 356 identifying 85 Valet de chambre. In addition to the former sampling set, and so as to detect a larger number of personages named as Valet de chambre, the Court Ordinances, and Prosopographia Burgundica as well as Prosopographia Curiae Burgundicae, were analysed. By utilising this method it was possible to identify 128 Valets de chambre attending at the Bourgundian Court during the studied period.

18Thanks to a second revision of the sources it was possible to find the first and the last mentions, and details about professions and other titles that the Valets de chambre had. For each personage, the catalogue sheet includes a specific set of fields : name, variations of the name, surname, variations of the surname, date of the first and the last documental reference to the person as Valet de chambre profession and the second title.

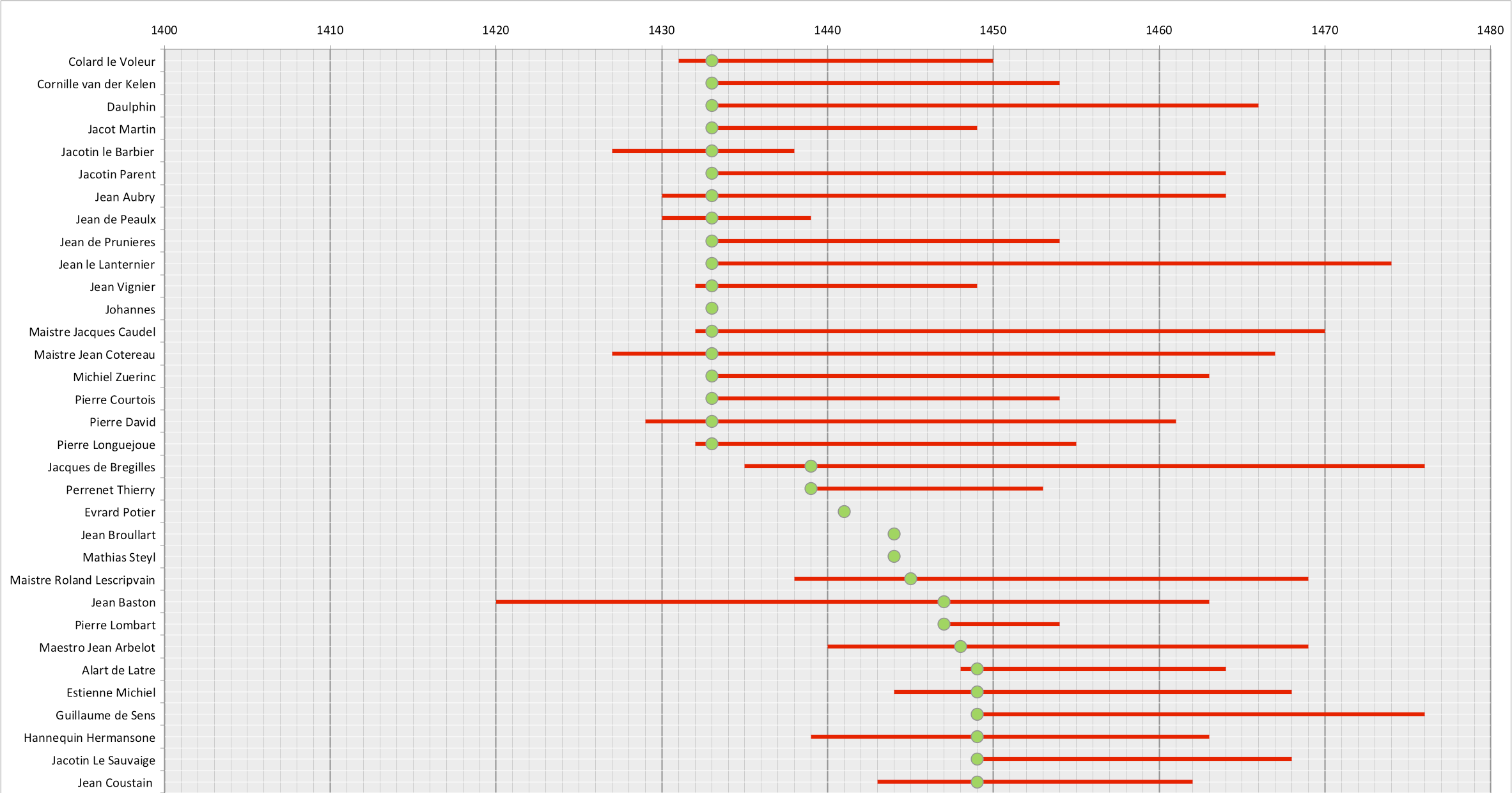

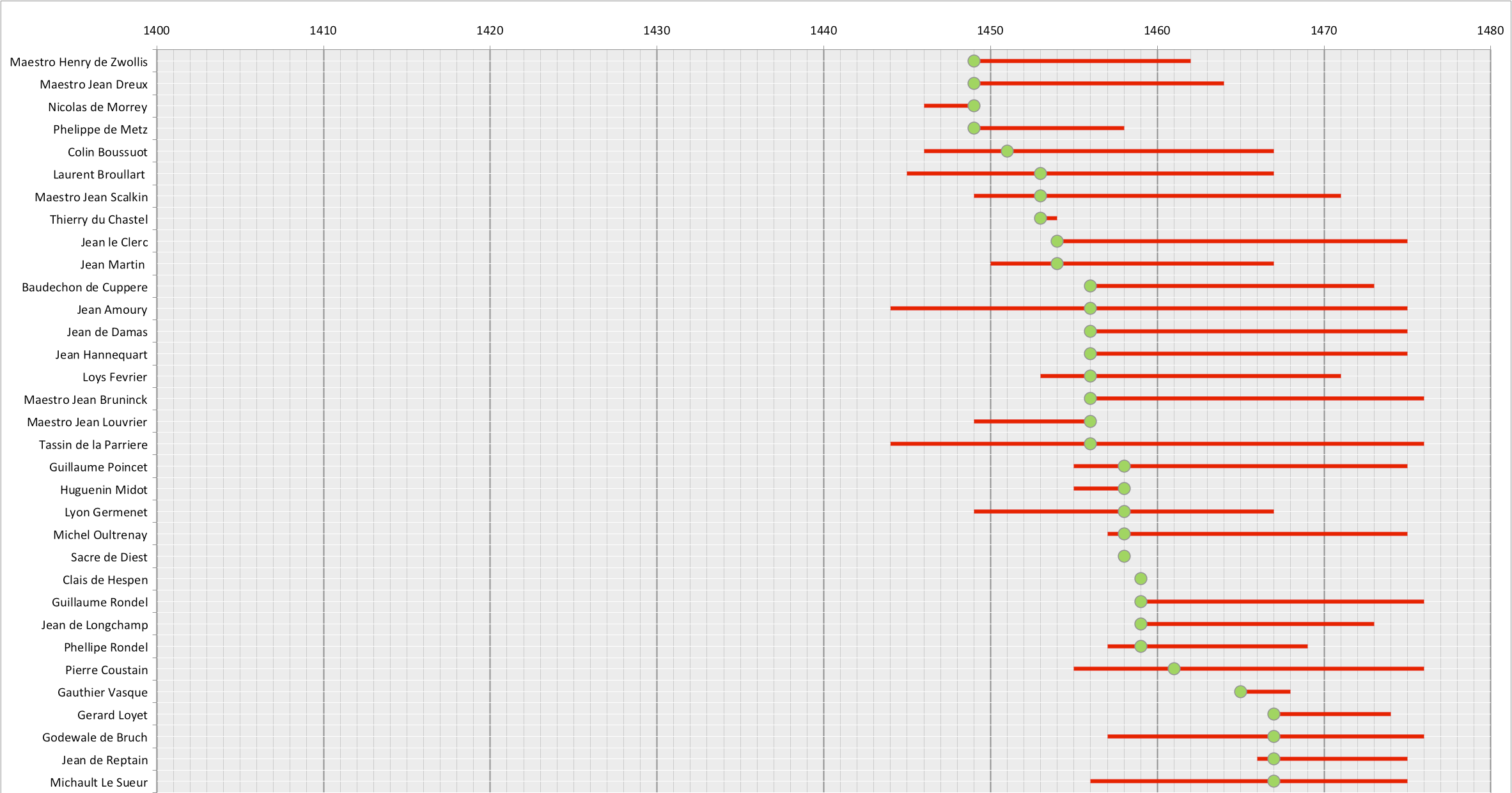

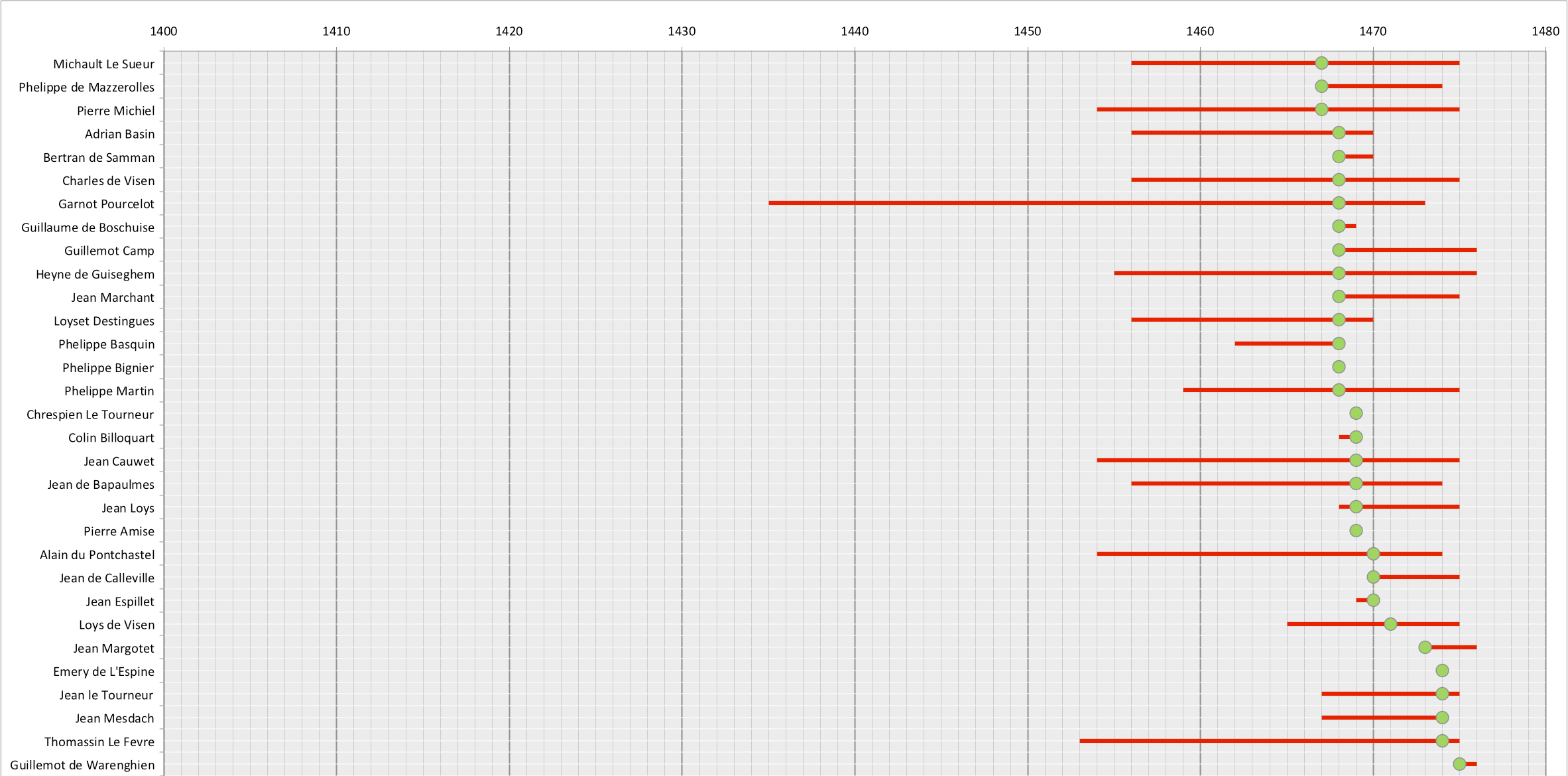

19The graphic resume of the collected data (Fig.1) is structured by year and by personages, marking their presence along the period (red segment). The chronological order follows the date of the first evidence when each dignitary was mentioned as Valet de chambre (green point). Furthermore, it is important to observe that only in few occasions the date marked by the green dot overlaps with the year of the dignitary’s appointment : like in the case of Guillaume Rondel whose nomination is documented the 20th of March 145926. This phenomenon is witnessed in the case of Guillaume Rondel, who we know due to the documental proof, was nominated on the 20th March 1459.

20The red segment joins the first and the last date in which documents referring to the personage were found. Nevertheless, some records, in which the mention Valet de chambre referred not directly to the dignitaries but to their familiars were not considered as a confirmation that the servant was still attending the court, and therefore they were excluded27. The red segment finishes at the year of the last mention found in the analysed corpus, but it does not represent the death date of the valet28.

21Concerning the continuity of the red segment, it should be clarified that Ordinances of the years 1426, 1427, 1433 and 1438 set different rules on the service shifts of the Valets de chambre. In particular, the first three Ordinances indicate three-month shifts, whilst the last one reports six-month shifts turning system29. Later Ordinances do not set any rules about turning. Notwithstanding the Ordinances, the analysis of the accounts shows that valets would receive orders and salary during the whole year in the whole studied period. As an example, Jehan Amoury, shoemaker and valet de chambre received orders and payments all throughout the year 146930.

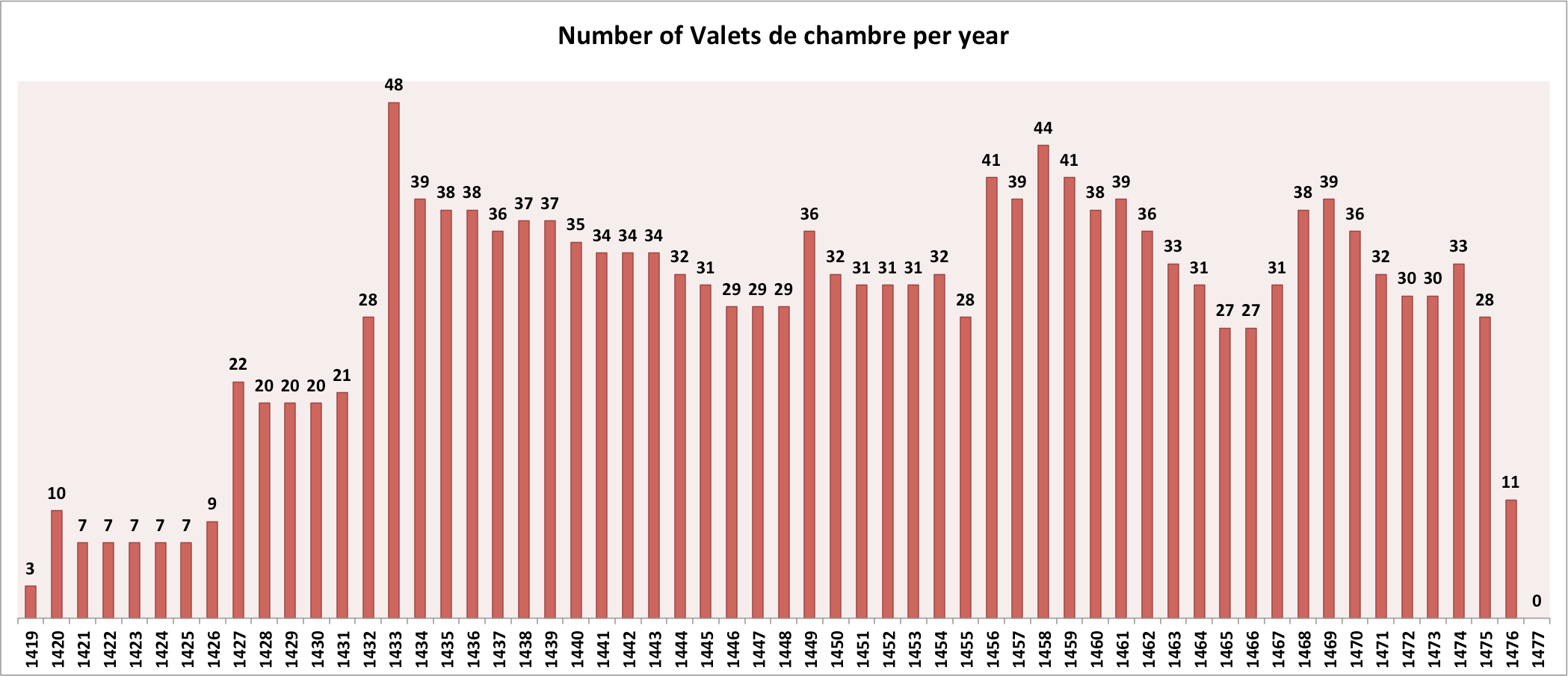

22In Figure 2 (Fig. 2), where the number of valets is arranged by year, two major breakdowns are visible in the first and the last year of the study31. Due to the lack of accounts, these two years cannot be considered descriptive of the court composition. Regarding the year 1419, it has to be considered that Philippe the Good inherited the duchy in September, after his father’s death, reducing the sampling set of documents to justifications of spent resources of the three last months of the year. The last years, instead, suffer from a serious lack of documentation of the Chambre des Comptes32.

23Generally the diagram shows the variability of the amount of valets derived from the character of the ducal court33. This fact is confirmed by Ordinances that explain that the duke had as many valets as he wanted and that they served in rotation :

24Mondit seigneur aura des valets de chambre telz qu’il lui plaira lesquelz serviront a tour, a chascune fois trois avec le premier valet de chambre et seront comptez chascun d’eulx deux chevaulx a gaiges et un varlet a livree34.

25Undoubtedly, the highest amount of valets was reported at the beginning of the 1430s, due to the improvement of the court structure and the writing of new complex ordinances in 1433. For this specific year the study identifies 48 servants with the title of Valet de chambre, even though the ordinance clarified :

26Item, aura mondit seigneur douze varles de chambre lesquelz serviront tousiours sans ordonnance avec les deux premiers varles de chambre qui serviront a tour de demi an en demi an…35.

27Nevertheless, with the exception of the twelve courtiers described in the introduction of the ordinance, the very same text cites another twenty six servants with the same title. Furthermore, according to various accounts, there were other valets working that year who were not mentioned by the Ordinance ; courtiers who had realized artistic tasks for the court in the years before and after the ordinance was writen, such as : Colard le Voleur (painter and architect)36, Perrot Broullard (tailor) 37, Jehan le Pestinien (manuscript illuminator)38, Johannes van Eck (painter)39, Thierry du Chastel (weaver)40, Karles Gilles (marchant of textils)41, Guillaume le Chasublier (tailor)42.

28From 1434 to 1456 it is possible to observe a slow decrease in the amount of servants (apart from the year 1449). As a matter of fact, the Ordinance from 1438 presented eight Valets de chambre and twenty-five other servants within the same rank. As in 1433, in 1438 five of the Valet de chambre documented in the accounts are in fact missing from the ordinance.

29From the late fifties a slow increase and then a decline of the quantity of servants until the death of Philippe the Good can be observed. On the contrary, the high amount of courtiers in 1468 derives from the succession of Charles the Bold who maintained the charge of the servants of his father and added the servants he had as Count of Charolais like Michiel Le Sueur43 or Gerard Loyet44. This action demonstrates the complete freedom of the duke in choosing the number of valets serving at his court, as stated in the ordinances. Moreover, Charles the Bold preserved the tendency dawned at the beginning of the fifteenth century of keeping a close influence to the court by appointing to the rank of Valet de chambre those professionals that did not proceed from the noble class, and allowing them to have access to the ducal apartments, trust and direct relationship with the duke45.

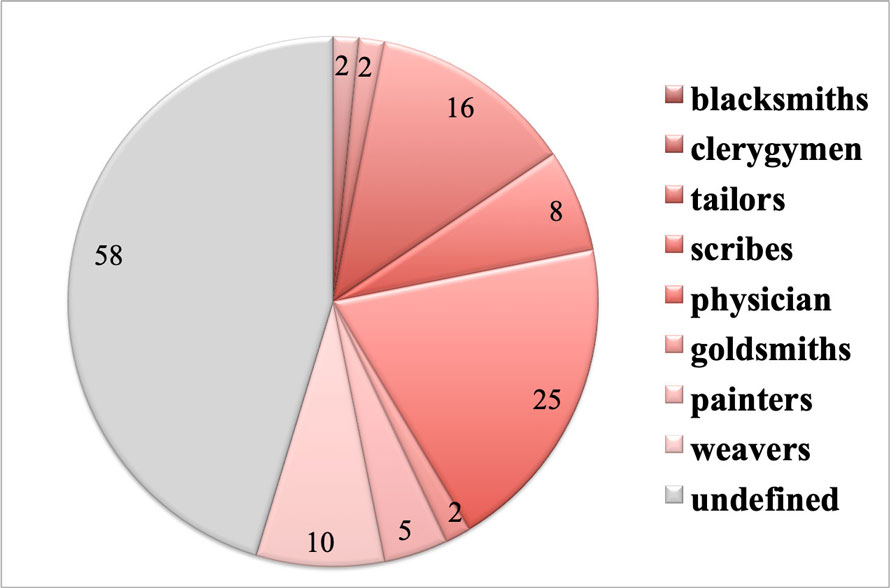

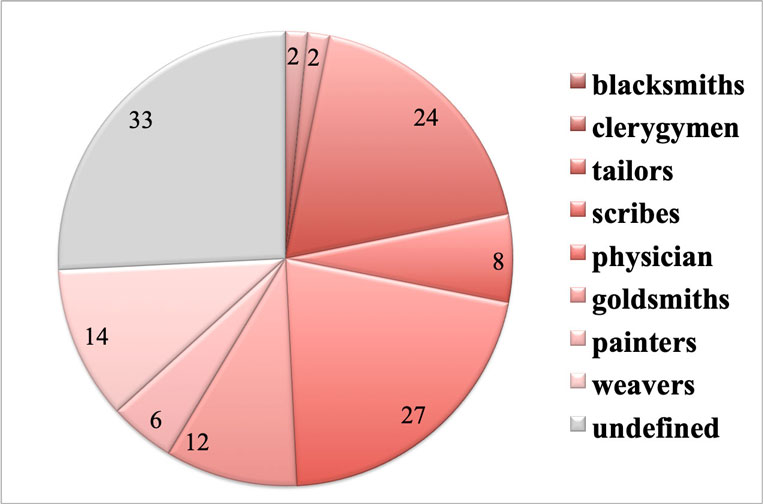

30The prosopographical approach and the identification of the 128 Valets de chambre allow an analysis of servants` professions that can be classified into nine different types (blacksmiths, clerygymen, tailors, scribes, physician, goldsmiths, painters, weavers and undefined) as shown in diagram 3 (Fig. 3). However, some types contain more than one profession, for instance « physicians » in which all the courtiers taking care of the health of the duke were combined (chirurgiens, barbiers, epiciers or apothicaires)46. The category « tailors » contains not only professions related to the production of ducal cloths but also shoemakers and leatherworkers47, while « weavers » form a different group as they are in charge of the creation or the restoration of tapestries and soft furnishings. Finally, the sub-type « scribes » contains writers, manuscript illuminators and poets like Michault Taillevant that is defined by sources as « le joueur de farses »48.

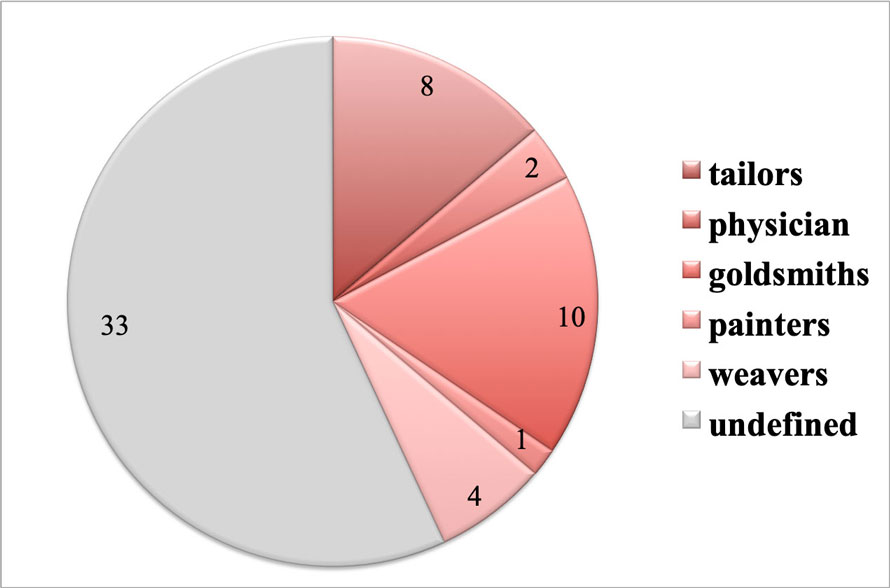

31Due to the high amount of indefinable professions, and in order to increase the knowledge about these personages, the second title appearing together with Valet de chambre was analysed. As a result Diagram 4 (Fig. 4) shows titles like : aide de spicier (physician), garde de banniers (painters), garde de joyaux, garde de robe, garde de tapisserie, sommerier du corps that was organized into previously defined proffesions according to the link that the titile has with the needed skill and finally undefined set. Additionally, only thirty three valets could not be identified as professionals49 but it seems reasonable to assume that all the other ranks required some skills or knowledge related to the profession already detected. Finally, the Diagram 5 (Fig. 5) shows the completed sample. The undefined valets could represent those valets cited by Olivier de la Marche who mainly served the duke with simple tasks and help him in his private chamber with daily activity50.

4. Conclusions

32Databases and statistics based on different types of documental sources made possible the identification of 128 valets de chambre of the Burgundian court from the period 1419-1477. Ordinances of the court fulfilled the study of the court expenses, although the lack of references’ made impossible to define the professional situation of all valets but the study allowed to collect and systematize a great amount of interesting personal facts about their life. Even if it was not posible to define all their proffesions, it is clear that those servants was an extreamly complex social group, made up of people with different occupations, associated by the possibility of participating in the court life without being noble.

33The narration of Olivier de la Marche indicates two different types of valets, professionals and simple servants. Also, the professional group list is not exhaustive since goldsmiths, weavers, scribes, working at the court around the year of redaction of l’Estat de la Maison du duc Charles de Bourgogne are not cited. To explain with detail the link between valets de chambre and the meaning of the Art at that time. The list provided by the chronicler should be complement by the data from the Chambre des Comptes. The second source indicates that many servants with the rank Valet de chambre are connected in a broad sense with the ducal artistic patronage. Those courtiers might have practiced their professions and also realised ducal orders at the court, such as painters, weavers, tailors, goldsmiths or scribes. However, the privilege of staying at court served to differentiate them from other artists and ingratiate them to the court structure. As a consequence, thanks to this privilege they could associate with the court and receive orders directly from the duke.

34Whilst the majority of valets cannot be interpreted as artists, it is still possible to observe that the title served to identify servants with some specific skill. Due to the plurality of the tasks and the relevance of valets de chambre in the court life, in order to gain access to that elite position, a craftsman and students very probably should have other skills and personal qualities beyond what can be mentiones the documents, such as an extraordinary personality, an unique knowledge of the market of his proffesion or the understanding of the finest political mecanisms. In fact, physicians, artists and tailors had to receive a specific education before attending the court, where they would work as specialists. Moreover, the mixed composition of this social group demonstrates that knowledge of medicine and artistic skill had somehow similar relevance and indicates that it was thought to be form of Art and specifys some factors for define « paragone » of art or consideration of the material worth of objects and services.

Fig. 1. Valets de chambre attending the court per year

Fig. 2. Number of Valets de chambre per year

Fig. 3. Professions of Valets de chambre

Fig. 4. Undefined Valets de chambre according to the second title

Fig. 5. Definitive diagram of Valets de chambre’s professions

Bibliographie

J. Archer Crowe, The Early Flemish Painters ; Notices of Their Lives and Works, London, 1872 (J. Murray).

L. Baveye, Exercer La Médecine En Milieu Princier Au XVe Siècle : L’exemple de La Cour de Bourgogne, 1363-1482, 2015 (Université Charles de Gaulle - Lille III).

M. Belozerskaya, Rethinking the Renaissance : Burgundian Arts across Europe, 2002 (Cambridge University Press).

S. Bepoix and F. Couvel, Rendre Bon Compte En Bourgogne À La Fin Du Moyen Âge : Le Dire Au Travers Des Ordonnances et Le Faire Selon Les Mots Des Receveurs, in Comptabilité(S), 4, 2012.

A. Châtelet, Un Brodeur et Un Peintre À La Cour de Bourgogne : Thierry Du Chastel et Hue de Boulogne, in Aachener Kunstblätter, 60, 1994.

A. Châtelet, Jean de Pestinien Au Service de Philippe Le Bon et de Son Prisonnier Le Roi René, in Artibus et Historiae, 20, 40, 1999.

P. Cockshaw, Le personnel de la chancellerie de Bourgogne-Flandre sous les ducs de Bourgogne de la Maison de Valois (1384-1477), Kortrijk, 1983 (Heule).

J. Dumolyn, Staatsvorming en vorstelijke ambtenaren in het graafschap Vlaanderen (1419-1477), Antwerpen, 2003 (Garant).

S. Fliegel, S. Jugie, and É. Antoine, L’art À La Cour de Bourgogne : Le Mécénat de Philippe Le Hardi et de Jean sans Peur (1364-1419) : Les Princes Des Fleurs de Lis, Paris, 2004 (Musée des beaux-arts de Dijon)

B. Fransen, Jan van Eyck, “el Gran Pin- Tor Del Ilustre Duque de Borgoña”. Su Viaje a La Península Y La Fuente de La Vida, in De Van Eyck a Rubens. La Senda Española de Los Artistas Amencos En El Museo Del Prado. Madrid, 2009, (Museo del Prado).

B. Fransen, Jan van Eyck Y España. Un Viaje Y Una Obra, in Anales de Historia Del Arte, 22, 39–58, 2010.

A. Hagopian Van Buren, The Hard Life of a Fifteenth Century Artist : Colard Le Voleur, in Miscellanea in Memoriam Pierre Cockshaw (1938-2008). Aspects de La Vie Culturelle Dans Les Pays-Bas Méridionaux (XIVe-XVIIIe Siècle), Aspecten van Het Culturele Leven in de Zuidelijke Nederlanden (14de-18de Eeuw), edited by F. Daelemans and A. Kelders, Bruxelles, 2009 (Bibliothèque Royale de Belgique).

S. Jolivet, Pour Soi Vêtir Honnêtement À La Cour de Monseigneur Le Duc de Bourgogne. Costume et Dispositif Vestimentaire À La Cour de Philippe Le Bon de 1430 À 1455, 2003 (Université de Bourgogne).

S. Jolivet, Justifier Les Dépenses Vestimentaires Dans La Recette Générale de Toutes Les Finances Du Duc de Bourgogne Philippe Le Bon, in Comptabilité(S), 4, 2012.

K. de Jonge, El Legado de Borgoña. Fiesta Y Ceremonia Cortesana En La Europa de los Austrias, in El Legado de Borgoña. Fiesta Y Ceremonia Cortesana En La Europa de Los Austrias, edited by K. de Jonge, B.J. García García, and A. Esteban Estríngana. Madrid, 2010 (Fundación Carlos de Amberes).

H. Kruse and W. Paravicini, Die Hofordnungen Der Herzöge von Burgund, Herzog Philipp Der Gute : 1407-1467, Stuttgart, 2005 (Thorbecke).

L. de Laborde, Les Ducs de Bourgogne. Études Sur Les Lettres, Les Arts et L'industrie Pendant Le XVe Siècle, Vol. 1, Paris, 1849 (Plon Frères).

S. Lindquisit, The Will of a Princely Patron and Artists and the Bourgundian Court, in Artists at Court. Image-Making and Identity 1300-1500, edited by Stephen J. Campbell, Boston, 2002, (Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, University of Chicago Press).

P. Lorentz, «Peintre et valet de chambre à la cour de France aux XIVe et XVe siècles: titre honorifique ou poste budgétaire ?», en The artist between court and city (1300-1600) = L’artiste entre la cour et la ville = Der Künstler zwischen Hof und Stadt, ed. Dagmar Eichberger, Philippe Lorentz, y Andreas Tacke (Peters- berg: Michael Imhof Verlag, 2017), 47-55.

Olivier de la Marche, Mémoires d’Olivier de La Marche Maitre d’Hotel et Capitaine Des Gardes de Charles Le Téméraire, Vol. 4, edited by H. Beaune, Paris, 1888 (Librairie Renouard).

A. Martinalde, The Rise of the Artists in the Middle Ages and Early Renaissance, London, 1972 (Thames and Hudson)

A. Michiels, Peintres Brugeois. Bruxelles, 1846 (Librairie Ancienne et Moderne de A. Vandale).

M. Mollat, Comptes Généraux de l’État Bourguignon Entre 1416 et 1420, Paris, 1965 (Imprimerie Nationale).

W. Paravicini, Structure et Fonctionnement de La Cour Bourguignonne Au XVe Siècle, in Publications Du Centre Européen d’Etudes Bourguignonnes, 28, 1988.

W. Paravicini, A. Greve, E. Lebailly, Comptes de l'argentier de Charles le Téméraire duc de Bourgogne, Vol. 1, Paris, 2001 (De Boccard).

W. Paravicini, A. Greve, E. Lebailly, Comptes de l'argentier de Charles le Téméraire duc de Bourgogne, Vol. 2, Paris, 2002 (De Boccard).

W. Paravicini, La Cour de Bourgogne Selon Olivier de La Marche, in Publications Du Centre Européen d’Etudes Bourguignonnes 43, 2003.

W. Paravicini, V. Bessey, V. Flammang, É. Lebailly, Comptes de l'argentier de Charles le Téméraire duc de Bourgogne, Vol. 3.1, Paris, 2008 (De Boccard).

W. Paravicini, V. Bessey, V. Flammang, É. Lebailly, Comptes de l'argentier de Charles le Téméraire duc de Bourgogne, Vol. 3.2, Paris, 2008 (De Boccard).

W. Paravicini, S. Hamel, V. Bessey, Comptes de l'argentier de Charles le Téméraire duc de Bourgogne, Vol. 4, Paris, 2009 (De Boccard).

B. Prost and H. Prost, Inventaires Mobiliers et Extraits de Comptes Des Ducs de Bourgogne de La Maison de Valois, T. II : Philippe Le Hardi, Paris, 1908 (Leroux).

B. Schnerb, L’État Bourguignon 1363-1477, 2005 (Perrin).

R.M. Tovell, Flemish Artists of the Valois Courts, 1950 (University of Toronto Press).

R. Vaughan, Philip the Good : The Apogee of Burgundy, Woodbridge, 2008 (The Boydell Press).

M. Warnke, The Court Artist : On the Ancestry of the Modern Artist, 1993 (Cambridge University Press).

D. Vanwijnsberghe, « Les enlumineurs des Pays-Bas méridionaux au service des ducs de Bourgogne de la Maison de Valois », 34-38 ; Céline Van Hoorebeeck, « Du “garde des joyaux de mondit seigneur ” au “garde de la bibliothèque de la Cour”. Remarques sur le personnel et le fonctionnement de la libraire de Bourgogne (XVe - XVIIe siècles) », en La librairie des ducs de Bourgogne : manuscrits conservés à la Bibliothèque royale de Belgique., ed. Bernard Bousmanne, Tania Van Hemelryck, y Céline van Hoorebeeck ( Turnhout: Brepols, 2009 ), 15-17.

H. van der Welden, The Donor’s Image. Gerard Loyet and the Votive Portraits of Charles the Bold, Turnhout, 2000 (Brepols).

This paper has been prepared thanks to a fellowship at the Université Catholique de Louvain granted by the University James I (Convocatòria d’ajudes per a realitzar estades temporals en altres centres d'investigació, per al personal docent i investigador de la Universitat Jaume 2016: E -2016 -09) and thanks to the advice from the Profesor Tania Van Hemelryck, who supervised my stay.

Notes

1 This paper has been prepared thanks to a fellowship at the Université Catholique de Louvain granted by the University James I (Convocatòria d’ajudes per a realitzar estades temporals en altres centres d'investigació, per al personal docent i investigador de la Universitat Jaume 2016: E -2016 -09) and thanks to the advice from the Profesor Tania Van Hemelryck, who supervised my stay.

2 M. BELOZERSKAYA, Rethinking the Renaissance: Burgundian Arts across Europe, 2002, p. 30–32.

3 An example of the artist honoured as « familia hospitii» was Giotto, serving at the court in Napels. A. MARTINALDE, The Rise of the Artists in the Middle Ages and Early Renaissance, London: Thames and Hudson, 1972, p. 36–37.

4 Ibid. p. 42.

5 J. ARCHER CROWE, The Early Flemish Painters; Notices of Their Lives and Works, London: J. Murray, 1872, p. 10–11. A. MICHIELS, Peintres Brugeois, Bruxelles, Librairie Ancienne et Moderne de A. Vandale, 1846, p. 13. L. DE LABORDE, Les Ducs de Bourgogne. Études Sur Les Lettres, Les Arts et L'industrie Pendant Le XVe Siècle, vol. 1, Paris: Plon Frères, 1849, p. 50.

6 B. PROST AND H. PROST, Inventaires Mobiliers et Extraits de Comptes Des Ducs de Bourgogne de La Maison de Valois, T. II : Philippe Le Hardi, Paris: Leroux, 1908, p. 239.

7 W. PARAVICINI « La Cour de Bourgogne Selon Olivier de La Marche », Publications Du Centre Européen d’Etudes Bourguignonnes, 43, 2003, p. 96.

8 OLIVIER DE LA MARCHE, Mémoires d’Olivier de La Marche Maitre d’Hotel et Capitaine Des Gardes de Charles Le Téméraire, vol. 4, edited by H. Beaune, Paris : Librairie Renouard, 1888, p. 18–19. Sophie Jolivet in her study analyses the structure of the ducal chambre and indicates details about some daily services of the valets de chambre: S. JOLIVET, Pour soi vêtir Honnêtement à la cour de monseigneur le duc de Bourgogne. Costume et Dispositif Vestimentaire À La Cour de Philippe Le Bon de 1430 à 1455, 2003, Université de Bourgogne, p. 293–302.

9 W. PARAVICINI, « Structure et Fonctionnement de La Cour Bourguignonne Au XVe Siècle », Publications Du Centre Européen d’Etudes Bourguignonnes, 28, 1988, p. 68.

10 Examples of prosopographical studies on the Burgundian Court : P. COCKSHAW, Le personnel de la chancellerie de Bourgogne-Flandre sous les ducs de Bourgogne de la Maison de Valois (1384-1477), Kortrijk : Heule, 1983, J. DUMOLYN, Staatsvorming en vorstelijke ambtenaren in het graafschap Vlaanderen (1419-1477), Antwerpen : Garant, 2003.

11 M. MOLLAT, Comptes Généraux de l’État Bourguignon Entre 1416 et 1420, Paris : Imprimerie Nationale, 1965.

12 W. PARAVICINI, A. GREVE, E. LEBAILLY, Comptes de l'argentier de Charles le Téméraire duc de Bourgogne, vol. 1, Paris: De Boccard, 2001, W. PARAVICNI A. GREVE, E. LEBAILLY, Comptes de l'argentier de Charles le Téméraire duc de Bourgogne, vol. 2, Paris: De Boccard, 2002, W. PARAVICINI, V. BESSEY, V. FLAMMANG, É. LEBAILLY, Comptes de l'argentier de Charles le Téméraire duc de Bourgogne, vol. 3.1, Paris: De Boccard, 2008, W. PARAVICNI, S. HAMEL, V. BESSEY, Comptes de l'argentier de Charles le Téméraire duc de Bourgogne, vol. 4, Paris: De Boccard 2009.

13 J. ARCHER CROWE, The Early Flemish Painters; Notices of Their Lives and Works, London: J. Murray, 1872, p. 10–11. A. MICHIELS, Peintres Brugeois, Bruxelles, Librairie Ancienne et Moderne de A. Vandale, 1846, p. 13. L. DE LABORDE, Les Ducs de Bourgogne. Études Sur Les Lettres, Les Arts et L'industrie Pendant Le XVe Siècle, vol. 1, Paris: Plon Frères, 1849. Laborde choosed by his cirteria accounts from the « Recette general des finances» for period from 1384 until 1477. This work considered his transcription of accounts for the period from 1421 until 1467.

14 More about « Recette general des finances» in: S. JOLIVET, « Justifier Les Dépenses Vestimentaires Dans La Recette Générale de Toutes Les Finances Du Duc de Bourgogne Philippe Le Bon », in Comptabilité(S), 4, 2012, S. BEPOIX AND F. COUVEL, « Rendre Bon Compte En Bourgogne À La Fin Du Moyen Âge : Le Dire Au Travers Des Ordonnances et Le Faire Selon Les Mots Des Receveurs », in Comptabilité(S), 4, 2012.

15 H. KRUSE AND W. PARAVICINI, Die Hofordnungen Der Herzöge von Burgund, Herzog Philipp Der Gute : 1407-1467, Stuttgart: Thorbecke, 2005.

16 Prosopographia Burgundica: http://www.prosopographia-burgundica.org/ (2017, March 10)

17 Prosopographia Curiae Burgundicae: http://burgundicae.heraudica.org/ (2017, March 10)

18 M. WARNKE, The Court Artist : On the Ancestry of the Modern Artist, Cambridge University Press, 1993, S. Lindquisit, « The Will of a Princely Patron and Artists and the Bourgundian Court », Artists at Court. Image-Making and Identity 1300-1500, edited by STEPHEN J. CAMPBELL, Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, University of Chicago Press, 2002.

19 R.M. TOVELL, Flemish Artists of the Valois Courts, University of Toronto Press, 1950, p. 33.

20 S. FLIEGEL, S. JUGIE, and É. ANTOINE, L’art À La Cour de Bourgogne : Le Mécénat de Philippe Le Hardi et de Jean sans Peur (1364-1419) : Les Princes Des Fleurs de Lis, Dijon: Musée des beaux-arts de Dijon, 2004, p. 167.

21 H. VAN DER WELDEN, The Donor’s Image. Gerard Loyet and the Votive Portraits of Charles the Bold, Turnhout: Brepols, 2000, p. 13.

22 B. FRANSEN, « Jan van Eyck, “el Gran Pin- Tor Del Ilustre Duque de Borgoña”. Su Viaje a La Península Y La Fuente de La Vida », De Van Eyck a Rubens. La senda Española de Los Artistas flamencos en El Museo Del Prado, Madrid: Museo del Prado 2009, p. 110–12; B. FRANSEN, Jan van Eyck Y España. Un Viaje Y Una Obra, in Anales de Historia Del Arte, 22, 39–58, 2010, p. 41–43.

23 D. VANWIJNSBERGHE, « Les enlumineurs des Pays-Bas méridionaux au service des ducs de Bo- urgogne de la Maison de Valois », 34-38 ; Céline Van Hoorebeeck, « Du “garde des joyaux de mondit seigneur ” au “garde de la bibliothèque de la Cour”. Remarques sur le personnel et le fonctionnement de la libraire de Bourgogne (XVe – XVIIe siècles) », en La librairie des ducs de Bourgogne : manuscrits conservés à la Bibliothèque royale de Belgique., ed. Bernard Bousmanne, Tania Van Hemelryck, y Céline van Hoorebeeck ( Turnhout : Brepols, 2009 ), 15-17.

24 In order to see the analysis of valets de chambre from the other courts, follow : P. Lorentz, « Peintre et valet de chambre à la cour de France aux XIVe et XVe siècles : titre honorifique ou poste budgétaire ?», en The artist between court and city (1300-1600) = L’artiste entre la cour et la ville = Der Künstler zwischen Hof und Stadt, ed. Dagmar Eichberger, Philippe Lorentz, y Andreas Tacke (Peters- berg : Michael Imhof Verlag, 2017), 47-55.

25 The research inclueds the most common forms of writing according to the « Dictionnaire du Moyen Français (1330 -1500) » of the title « Valet de chambre »: varlet de chambre, vallet de chambre and vaslet de chambre. http://atilf.atilf.fr/ (2017, March 10)

26 H. KRUSE AND W. PARAVICINI, Die Hofordnungen Der Herzöge von Burgund, Herzog Philipp Der Gute : 1407-1467, Stuttgart: Thorbecke, 2005, para. 625. Brüssel, AGR, Audience, Cedules, Nr. 904.

27 Like in the case of Jean van Eyck, the duke paid to his daughter for celebrate the mass in his name in 1449. Archer Crowe, The Early Flemish Painters; Notices of Their Lives and Works, London: A. MICHIELS, Peintres Brugeois, Bruxelles: Librairie Ancienne et Moderne de A. Vandale, 1846, p. 13. L. DE LABORDE, Les Ducs de Bourgogne. Études Sur Les Lettres, Les Arts et L'industrie Pendant Le XVe Siècle, vol. 1, Paris: Plon Frères, 1849, para. 1407.

28 There is none identified document that can describe circumstance the dismissal of some valet de chambre.

29 H. KRUSE AND W. PARAVICINI, Die Hofordnungen Der Herzöge von Burgund, Herzog Philipp Der Gute : 1407-1467, Stuttgart: Thorbecke, 2005, p. 68, 132, 178.

30 W. PARAVICINI A. GREVE, E. LEBAILLY, Comptes de l'argentier de Charles le Téméraire duc de Bourgogne, vol. 2, Paris : De Boccard, 2002, para. 1413, 1443, 1461, 1485, 1572, 1593.

31 The first decades of Philippe the Good’s duchy show that the circle of valets was limited.

32 W. PARAVICINI, V. BESSEY, V. FLAMMANG, É. LEBAILLY, Comptes de l'argentier de Charles le Téméraire duc de Bourgogne, vol. 3.1, Paris: De Boccard, 2008, p. XIX.

33 W. PARAVICINI, « Structure et Fonctionnement de La Cour Bourguignonne au XVe Siècle », Publications du Centre Européen d’Etudes Bourguignonnes, 28, 1988, p. 68.

34 H. KRUSE AND W. PARAVICINI, Die Hofordnungen Der Herzöge von Burgund, Herzog Philipp Der Gute : 1407-1467, Stuttgart: Thorbecke, 2005, p. 68.

35 Ibid., p. 122–23.

36 Colard le Voleur was a responsable person of the renovation of the Castle of Hesdin, he is mentioned in the ducal accounts between 1431 and 1454 as « Valet de chambre ». More about his Works and his life in: A. HAGOPIAN VAN BUREN, « The Hard Life of a Fifteenth Century Artist: Colard Le Voleur », Miscellanea in Memoriam Pierre Cockshaw (1938-2008). Aspects de La Vie Culturelle Dans Les Pays-Bas Méridionaux (XIVe-XVIIIe Siècle), Aspecten van Het Culturele Leven in de Zuidelijke Nederlanden (14de-18de Eeuw), edited by F. DAELEMANS AND A. KELDERS, Bruxelles: Bibliothèque Royale de Belgique, 2009.

37 Mentioned as a servant of the court between 1432 and 1449. He has recived the salary for preparation of cloths and textils with the occasion of the ducal weding and assambleas of the Order of the Golden Fleece. J. ARCHER CROWE, The Early Flemish Painters; Notices of Their Lives and Works, London: J. Murray, 1872, p. 10–11. A. MICHIELS, Peintres Brugeois. Bruxelles: Librairie Ancienne et Moderne de A. Vandale, 1846, p. 13. L. DE LABORDE, Les Ducs de Bourgogne. Études Sur Les Lettres, Les Arts et L'industrie Pendant Le XVe Siècle, vol. 1, Paris: Plon Frères, 1849, para. 1056.

38 Active at the court in 1443, an autor of some iluminations of the « Grandes Heures of Philippe le Hardi» more about his oeuvre: A. CHÂTELET, « Jean de Pestinien Au Service de Philippe Le Bon et de Son Prisonnier Le Roi René », Artibus et Historiae, 20, 40, 1999.

39 He has recived salaries from the duke according to the accaounts of Laborde between 1425 and 1435.

40 He has been active at the court between 1432 and 1458. Hipotetical author of the paraments of the Golden Fleece : A. CHÂTELET, « Un Brodeur et un Peintre à la Cour de Bourgogne : Thierry Du Chastel et Hue de Boulogne », Aachener Kunstblätter, 60, 1994.

41 Marchant of textiles from Lucca, active at the court in 1432.

42 He has served at the court of Isabel of Portugal between 1423 and 1430 and than at the ducal court until 1435.

43 He served from 1456 at the court of Count of Charolais and in June of 1467 he passed to the Hôtel of the duke. Lille, ADN, B3421, no. 116989. Lille, ADN, B3431, no. 118450.

44 Gerard Loyet for the first time is mentioned in May of 1467 at the « Hôtel» of the Cout of Charolais, in July he passed to the court of the duke Charles the Bold Lille. ADN, B3431, no. 118438. Lille, ADN, B3431, no. 118450.

45 B. SCHNERB, L’État Bourguignon 1363-1477, Perrin, 2005, p. 298; K. DE JONGE, El Legado de Borgoña. Fiesta Y Ceremonia Cortesana En La Europa de los Austrias, « El Legado de Borgoña. Fiesta Y Ceremonia Cortesana En La Europa de Los Austrias », edited by K. DE JONGE, B.J. GARCÍA GARCÍA, and A. ESTEBAN ESTRÍNGANA. Madrid: Fundación Carlos de Amberes, 2010, p. 65.

46 More details about tasks and clasification of phisicians at the Burgundian Court in : L. BAVEYE, Exercer La Médecine en Milieu Princier au XVe Siècle : L’exemple de La Cour de Bourgogne, 1363-1482, 2015, Université Charles de Gaulle - Lille III, p. 82–94.

47 Details about artisanals that produced cloths for the ducal « Hôtel» in : S. JOLIVET, Pour soi vêtir Honnêtement à la cour de monseigneur le duc de Bourgogne. Costume et Dispositif Vestimentaire À La Cour de Philippe Le Bon de 1430 à 1455, 2003, Université de Bourgogne, p. 293–302.

48 L. DE LABORDE, Les Ducs de Bourgogne. Études Sur Les Lettres, Les Arts et L'industrie Pendant Le XVe Siècle, vol. 1, Paris: Plon Frères, 1849, para. 942. Michault Taillevant in every ordinances is mentiones separatly from others valets as « le joueur de farses», it seems to emphasize his role.

49 Undefined personal : Albrecht van Driel, Baudechon de Zoppere, Bernard de l'Olive, Chrespien Le Tourneur, Colin Billoquart, Emery de L'Espine, Ernoul Clotin, Guillaume Poincet, Huguenin Midot, Hustin de Thiembronne, Jacotin Le Sauvaige, Jean de Damas, Jeannin Bacheler, Jehan de Calleville, Jehan de Prunies, Jehan de Reptain, Jehan Espillet, Jehan Margotet, Jehan Martin, Jehan Mesdach, Jehan Vignier, Loys Fevrier, Mahiet Regnault, Michelet du Bois, Phelippe Basquin, Phelippe Bignier, Pierre Amise, Pierre Courtois, Pierre David, Pierre Longuejoue.

50 OLIVIER DE LA MARCHE, Mémoires d’Olivier de La Marche Maitre d’Hotel et Capitaine Des Gardes de Charles Le Téméraire, vol. 4, edited by H. Beaune, Paris : Librairie Renouard, 1888, p. 18–19.

L'auteur

L'auteur

University of Silesia, Katowice, Poland. Instituto Moll. Centro de investigación de Pintura Flamenca, Madrid, Spain.